Lovely new write up for Suffolk Ghost Tales, with an interview Cherry and I did with Sheena Grant of the East Anglian Daily Times:

All posts by KirstyTHartsiotis2

Holiness and profanity? A visit to Cerne Abbas

We all know what to expect from Cerne Abbas, don’t we? A picture speaks a thousand words on this one. Shall I give you a close up? No? We all know that by the 19th century he was associated with fertility and that it’s said that as a woman either sleeping alone in the phallus or, er, doing a bit more than sleeping there with your partner can cure infertility. No surprises there… But there’s another fertility boost in the very same village, and this one was probably the one used in the medieval period, and, perhaps, before.

Why? Well, if you go, as Anthony and I did this last weekend, to see the giant from the viewpoint, the text panel tells you that the Cerne Abbas giant may be one of the three ancient chalk figures of England – made, unlike most of the chalk horses and etc., before the Middle Ages. The others are, of course, the Uffington White Horse, which may be up to 3000 years old, and the Long Man of Wilmington, which, is now considered to be probably a lot newer than previously thought, not Iron Age, but 16th or 17th century – possibly much like the Cerne Abbas giant. Unlike the Uffington horse, which is first mentioned in the 11th century, there are no mentions of the two human figures before the 17th century, Cerne Abbas first appearing in 1694 and Wilmington in 1710. The giant might, in fact, be a bawdy caricature of Oliver Cromwell as Hercules (he once had a cloak as well as a club, now obliterated) put there by Lord Holles, the Lord of the Manor.

Holles was a Parliamentarian, but a moderate – he hated Cromwell and the army party, and accused him of cowardice. In the complicated times towards the end of the wars, he held fast to his moderate views, begging the king to reconsider. Sadly, neither the king nor Cromwell were moderates, and Holles’ faction was doomed to failure. He was, however, one of the leading people who brought about the Restoration. We will probably never know if he had the giant cut, however, as the first suggestion of this was in the 1770s, nearly a century after his death.

How it was cut and why are lost. If you do get close to it, it’s hard to see how the figure fits together. Anthony walked up the hill, and said that he could just see the horizontals… He didn’t cross the barbed wire into the giant’s enclosure, however. I busied myself with some anthropomorphic flowers instead, the fine Early Purples growing there.

If only they had been Monkey Orchids – much more fitting! (These from a site near Megalopolis on the Peloponnese, though there are a very few sites here in England, there are none recorded in Dorset)

But what about that other fertility place? I had no idea that we were going to get a double folklore whammy from the place when we arrived. Obviously, I knew there had been an abbey there (here’s the site of it – really not a single stone left of the church) but what I didn’t know was the story of its foundation, and why. Indeed, on the OS 1:50000 map, there is no indication that there is an ancient holy well just down from the burial ground of the parish, below where the abbey once lay. It’s there on the 1:25000, but we didn’t have that.

Oddly, there are two conflicting stories as to how the spring was discovered. In the seeming first, it’s St Augustine (of Canterbury, I assume?) who happened to be travelling there. He chanced upon some shepherds, and asked them if they wanted beer or water to drink – and on their saying ‘water’, he struck the ground with his staff and up bubbled a spring. As he struck the ground he cried out ‘Cerno El!’ – ‘I see God!’, a pun on the name of the village, Cernel … thus continuing the great saint punmeister tradition (see St Gregory’s quip ‘non angli, sed angeli’ when seeing English men at a slave market). This, if true, presumably happened at some point in the very early 7th century when Augustine was archbishop.

But, unfortunately, this tale was concocted by the monks of Cerne Abbas in the 11th century. Cruising around the country at that moment was Gotselin, a roving hagiographer – William of Malmesbury says of him, ‘He went over the bishoprics and abbeys for a long time, and gave many places monuments of his surpassing knowledge.’[i] – who happened to be the first hagiographer of Augustine of Canterbury. The first archbishop of Canterbury was a far more exalted founder, the monks evidently thought, than the man who may really have discovered the spring.

The text panel at the well says that the next tale is ‘truth’, but we must be cautious with that – especially as we don’t really know whether this man definitely existed. St Eadwold may – or may not – have a Suffolk connection. He may be the brother of St Edmund, but managed to sensibly skip off out of East Anglia before his brother was killed by the Vikings and make his way to Dorset. On his way, he had a vision of a silver well, and started trying to follow a path to it. On arriving at Cernel he gave a shepherd some pennies – which were, of course, silver in those days – for bread and water, and the shepherd took him to a well. Eadwold recognised it as the one in his vision, and built a hermitage there – though it might not have been at the spring, but on a hill nearby (Giant Hill, anyone?), and he worked many miracles (though I don’t know whether they were before or after he died … O for access to the Journal of Medieval Latin!) He probably died about 900AD, and a swift 70 years later the Benedictine monastery was founded. Of course it’s possible that the well was both struck by Augustine and rediscovered by Eadwold … and used by the shepherds throughout.

But what about that fertility stuff? There are a number cures attributed to the well – it’s good for eyes and newborns as well as curing infertility. It’s also a wishing well, with girls instructed to place their hands on the wishing stone and pray to St Catherine for a husband (there was a St Catherine’s chapel just up the hill). A more sinister superstition is that if you look in the well first thing on Easter Day, then you will see those who will die that year reflected back up at you…

As for chalk figures, even if we don’t have the chalk in Suffolk, we can still do the job… Is the figure of the Suffolk Black dragon still at Bures?

[i] Anon ‘Goscelin or Gotselin, (fl 1099)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/odnb/9780192683120.001.0001/odnb-9780192683120-e-11105

Information about the well from the village text panel and from Harte, J M Dorset Holy Wells: http://people.bath.ac.uk/liskmj/living-spring/sourcearchive/fs1/fs1jh1.htm

The Treasure Seekers: finding (or not) gold and wealth in local folklore

If there’s one trope of folklore that appears over and over again, it’s schemes to get rich quick. Jack and the Beanstalk is, of course, one of the most universal – who wouldn’t want a goose that laid golden eggs? Lazy but often kind boys charm princesses into marrying them; pretty and resourceful maids do the same with princes. These fairy tales are a daydream, a wish-fulfilment to those stuck in a seemingly inescapable round of poverty and want. It’s something we can easily recognise in lottery ticket buying and the poring over the lives of celebrities and the royals even as austerity pinches pockets a little further and privatisation erodes the services we once had. But get rich quick stories didn’t always take place in the never-never land of fairy tales. Sometimes they take place right here, in our local area.

In researching the various folk and ghost tale books I’ve written, these tales occur again and again. They are not, of course, tales in which people actually get rich quick. These are the other sort – the sort that tells us not to rock the boat, not to disturb the status quo, to knuckle down and work hard to get your rewards because these schemes always end, if not in disaster, then in disappointment.

You see, there’s treasure hidden out there, under the earth, in ponds, in secret places. We all know it’s true – look at Lance and Andy in Detectorists sweeping their metal detectors over the (allegedly) Essex countryside (actually Suffolk!) and, at the series’ end, discovering the treasure lurking beneath their feet. People have been discovering this hidden treasure for centuries – Roman coin hoards, lost rings, real buried treasure placed with the pagan dead. Even now, we are desperate to concoct tales to tell the story of why this treasure happened to be where it was, even if our tales today tend to be more historically minded than the tales told in ale houses and by firesides in the day’s before we knew the history in the earth. But still, stories they are.

That’s why it’s thrilling to think that the man in Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo might actually be King Raedwald. A real person, attested by that reliable witness, Bede – and in king lists. We already have a story to attach to him. But there is a tale that Edith May Pretty, who owned the estate that the burial ground sits on back in the 1930s, had a friend who saw ghosts there – including one who stood on Mound 1, which, so it’s said, inspired Pretty to get the archaeologists in, just before the Secord World War![i] Of course, there may have long been tales that the burial mounds were haunted – after all, most of them had been ransacked for the treasure that the robbers had failed to find in Mound 1.

Not surprisingly, burial mounds are often a focus of treasure seeking tales. Not just Anglo Saxon and Bronze Ages ones, potentially likely to hold treasure, but the far older long barrows, which were repositories for bones, not the metal whose use had not yet been discovered by the people who raised them. As I’ve said before, often all these mounds were thought to be Saxon or Viking, so Molly the Dreamer of Minchinhampton can meet a Saxon warrior under Gatcombe Tump long barrow on his dreamed tip off that there’s gold buried there, as retold in Gloucestershire Ghost Tales. But that’s only one example – there’s a Bronze Age round barrow near Bisley, also in Gloucestershire, that’s actually called Money Tump! The tale there, retold by Westwood and Simpson, is that it was well-known that there was treasure there – a farmer wished to bulldoze the mound to find it, saying he’d ‘be rich for the rest of his life.’ [ii] The money came from the chieftain buried there after, presumably, being cut down fleeing the invading Saxons. There have been sightings of headless warriors there, too, though admittedly this was after the Bisley Feast…[iii] There’s a Golden Coffin Field up there, too, at Oakridge, with a tale that the field once contained such a thing – there’s a barrow in the field.[iv]

In Wiltshire there’s a golden coffin, too, but with a darker tale attached to it. It’s associated with one of the barrows on the Down at Bowerchalke, near Salisbury. I tell the tale in Wiltshire Folk Tales, and there are usual admonitions of not speaking while raising the coffin – but of course one of the seekers does, and the seven men who went up the hill to dig up the coffin never came down, but rather roam the hill, dragging the coffin behind them – its theirs for eternity, but not in this life! A tale told to put you off, to deter you from going up the hill and trying your luck! Treasure sits under megaliths, too – such as in Somerset under the wandering Wimblestone[v] – if you can get your hand under there while it’s dancing around the field at full moon and Midsummer’s Eve, or rolling down to meet the nearby Water Stone… What won’t work is yoking horses to it to move it during the day – the Wimblestone mocks you by staying put, then mocks you all the more by telling the tale to the Water Stone when next they meet!

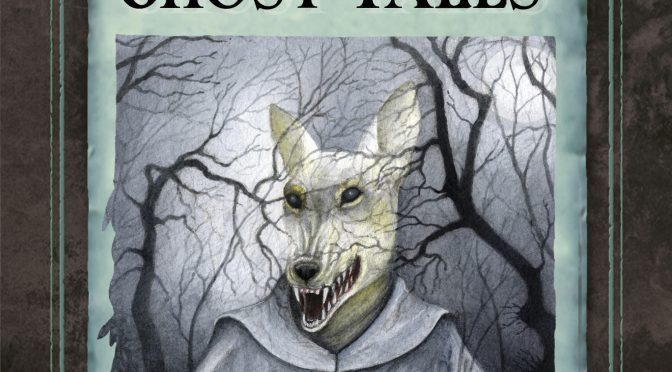

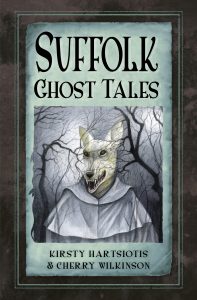

It isn’t just mounds and stones were treasure can be found, back in Suffolk again we find our poster boy, who graces the cover of Suffolk Ghost Tales – the Dog-headed monk (and his nearby fellow, the Monk-headed dog), who is the ultimate odd couple – a monk and dog set to guard a treasure by St Felix, the bringer of Christianity to Suffolk at one of Suffolk’s many Clopton’s that have strangely morphed over the centuries into one being… These creatures are by halls – places of the wealthy, where you might logically think there would be treasure to be found.

Pools are another likely location – makes sense, we love putting treasure in water, a relict of a time in the Bronze Age when we offered sacrificial weapons to the spirits, maybe, of the water, and seen in every penny dropped into fountains around the world to ensure a wish come true or a return visit. At Wimbrell Pond near Long Melford is a sorrowful husk of a ghost who clings to its treasure, calling out, ‘that’s mine,’ when people try to retrieve it – although the pond may be long gone now, and the treasure forgotten. It’s said that there was a major Roman vs Celt battle there, on the Roman road to Coddenham, and that maybe the ghost has been there since then.[vi]

Even if you get the treasure in your hands of a night it will be gone by morning – as evinced by the case of the old lady of Orford who was buried with her gold and sent out of her grave to try to give it away as a punishment for trying to hang onto it when we all knew that, despite what the ancients might have thought, you can’t take it with you. But ghostly gold only exposes the gullibility and avariousness of those who seek it…

What can we draw from all these tales, and the many, many more that I could mention? I don’t know, but I do wonder whether if our society was more equal and wealth distributed so that we were more comfortable, whether we would dream of free wealth in this way and go to the great efforts our folkloric cousins go to get the free thing? Hmm. Back to Lance and Andy again. Much treasure dug up now does go into museums for all of us to see, but what drives the people who seek for it? Are they content with finding the fragments of the past for the thrill of meeting the ancestors? Many are. But – you do get paid the worth of treasure if you find it – divided between the finder and the landowner. And that is a driver as well. And, all of us, we know the excitement of finding a pound coin (not so much a penny, these days, for all the luck it might bring) or more dropped by another…

Images:

1. Cover image for Suffolk Ghost Tales (c) Katherine Soutar-Caddick

2. Sutton Hoo in the snow (c) Kirsty Hartsiotis

3. Wolfhang from Molly the Dreamer (c) Kirsty Hartsiotis

4. The Barrow Thieves (c) Kirsty Hartsiotis

5. Orford churchyard – where the old lady is said to be buried (c) Kirsty Hartsiotis

Notes:

[i] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUG2LqqsEek

[ii] Westwood, J & Simpson, J The Lore of the Land (Penguin Books, 2005), p. 283

[iii] Rhiannon http://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/4614/money_tump.html

[iv] Grinsell, L V The Ancient Burial Mounds of England (Routledge, 2015), p. 68

[v] Grinsell, L V Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain (David & Charles, 1976), p. 58 & 104

[vi] Burgess, Mike Hidden East Anglia, https://www.hiddenea.com/suffolka.htm#acton

Ghosts of the Mounds: prehistory and ghostlore in Gloucestershire and Wiltshire, a beginning

Lately, I’ve been intrigued by the different ghosts that emerge from the many, many prehistoric barrow mounds in the west. I’m doing talks on Gloucestershire’s ghosts and Wiltshire’s folklore, and I’ve been reminded of how, here in the west, they form an important part of the folklore of the region. This blog, probably the first of a few, explores some of the hauntings and their tales – if you’d like the full tales, you’ll find some of them in my books Wiltshire Folk Tales and Gloucestershire Ghost Tales.

Ghosts, fairies or giants? The case of Hackpen Hill

Back in antiquarian John Aubrey’s time, the 17th century, the mounds and the downland on which they were situated were things to be feared. In the long barrows, giant’s bones resided, and the very ground could open up and take you – like these incidents on Hackpen Hill near Avebury:

‘Some were led away by the Fairies, as was a Hind riding upon Hakpen with corne, led a dance to the Devises. So was a shepherd of Mr. Brown, of Winterburn-Basset: but never any afterwards enjoy themselves. He sayd that the ground opened, and he was brought into strange places underground, where they used musicall Instruments, violls, and Lutes, such (he sayd) as Mr. Thomas did play on.’[i]

Aubrey collected these snippets in his collection Remaines of Gentilisme and Judaisme, of 1686-7 – but not published until 1881 by the Folklore Society. It is a collection of folklore from all over Europe, collected together willy-nilly, with a little local lore slotted in. Aubrey recorded that the people in the area thought that the long barrows around were the graves of giants. Round barrows were easily recognised as graves, too. Aubrey records that on Hackpen Hill ‘in a barrow … after digging, was found at thigh-bone of a man and several urns’. Many people at that time believed that what they were finding were the remains of Saxons and Vikings in these mounds. In some cases, of course, this was true – also on Hackpen Hill in the late 19th century Canon Greenwell, ‘a prolific excavator of barrows’, found evidence of the reuse of a Bronze Age barrow, finding a later Saxon inhumation with an iron spear over a cremation burial with a bronze dagger[ii]. Aubrey and his contemporaries were hindered by the lack of knowledge that there had been earlier cultures in Britain than that of the Iron Age that the Romans encountered and wrote about. Geoffrey of Monmouth explains away Stonehenge by ascribing it to Merlin’s magic (and giants in Africa … but that’s another story) but Aubrey and his contemporaries realised it and the other standing stones and burial mounds were much earlier, his generation creating a long-lasting misconception about druids and stone circles that still continues in the national psyche.

The haunting of the Woeful Dane

The idea, though, that it was Saxons and Vikings in the mounds lingers… In Gloucestershire, one of my out and out favourite stories is that of Molly the Dreamer of Minchinhampton, who encounters the ‘Woeful Dane’ (actually a Saxon) who is said to have named Woefuldane’s Bottom near the Long Stone. He was Wolfhang, and his shade haunts the lane. To Molly, though, he promised aid in the form of the glittering gold hidden in his grave – I won’t tell the tale, it’s in Gloucestershire Ghost Tales – but suffice to say that she didn’t get it! Sadly, the great battle where the Saxons under Wolfhang routed the Danes exists only in the imagination of the people of Minch – the name Woefuldane probably derives from a place where a wolf was caught[iii] … although that might shed some light on the see-through, headless black dog that also haunts the lane, and who caused carters in the 19th century to insist on being blindfolded on that stretch of road at night, lest they see its insubstantial form. Gatcombe Tump, Wolfhang’s mound, is a Cotswold-Severn type long barrow – dating from the early Neolithic, about 3500BC.

‘She did come out of the mound’

In the story at Manton barrow, near Marlborough, the tale goes that a finger bone was borrowed by a journalist after the excavation in the early 20th century, and when taken to a séance, a wronged Saxon princess was conjured up by the medium! Manton barrow is a round barrow in which were found the remains of ‘a woman of considerable age, and that their period was somewhere during the latter portion of the Bronze Age.’[iv] But there is a coda that seems more real. The grave goods were taken to Devizes Museum, but the skeleton was returned to the grave. Soon after, a woman of the village complaining to her doctor: ‘every night since that man from Devizes came and disturbed the old creature she did come out of the mound and walk around the house and squinny into the window. I do hear her most nights and want you to give me sammat to keep her away.’[v] Alcohol is secretly prescribed, and the old woman sleeps soundly from then on but I feel sorry for the lonely ‘old creature’, perhaps only seeking companionship after her lonely grave was disturbed and her spirit released.

‘I suddenly saw before me a long barrow’

The idea that the spirits of the dead are disturbed by excavation can also be seen in the tales of ghosts around the hard to find West Tump. Another Cotswold-Severn long barrow, it was discovered by the well-known Gloucestershire archaeologist, G B Witts, by accident while on a Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society outing in 1880. Witts, on horseback as opposed to in a carriage, took a shortcut through Buckholt Woods, and as he was riding through the portion the OS map calls Buckle Wood, with, as he says, ‘my mind intent on archaeology, and I suddenly saw before me a large barrow!’[vi] The barrow was duly excavated, the innumerable human remains removed in this case to the museum at Cheltenham, and, in time, nature covered the mound once more. But the people knew that the spirits were restless, and figures began to be seen around the mound, figures in leather cloaks, inked with tattoos and bearing stone-tipped spears. The ghosts in these last two stories, both from an era when people knew more about the pre-history of Britain, are more up to date, the ghosts seemingly reflecting the real occupants – or at least people’s imagined ideas of them.

It seems we create our ghosts anew with every generation, assimilating new information. What ghosts do the mounds conjure a hundred years on from the excavation of Manton Barrow? The mounds are now more in use than ever, visited by walkers and the curious – and by modern pagans honouring the ancestors and reinventing and imagining what might have happened when the original dead were laid to rest. But we know not what expectations the makers of the mounds had. Did they expect the spirits of their ancestors to lie quietly, as we expect of the dead today, or did they envisage a more active role for the spirits, perhaps, in the Bronze Age at least, still working to protect the living – many round barrows are placed on hills and ridges, or on boundaries. Were they set there to guard the land and the people in some way? What then if the barrow is disturbed? We can imagine that there would be dire consequences in the stories of the folk who raised the mounds… Did those stories linger? Perhaps it’s no wonder that the idea of ghosts – or fairies – in the mounds has come down over the centuries even to our materialist age.

Images:

- Featured image: Gatcombe Tump, near Minchinhampton © Kirsty Hartsiotis, 2014

- A view of Hackpen Hill, near Winterbourne Bassett

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Brian Robert Marshall – geograph.org.uk/p/1010217 - Wolfhang © Kirsty Hartsiotis, 2015

- The ‘Old Creature’ © Kirsty Hartsiotis, 2011

- West Tump ( Long Barrow )

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Michael Murray – geograph.org.uk/p/937490

References:

[i] Britton, John, ed. The Remaines of Gentilisme and Judaisme by John Aubrey RSS 1686-87 (The Folklore Society, 1881), p. 30

[ii] http://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/4598/hackpen_hill_wiltshire.html

[iii] Palmer, Roy The Folklore of Gloucestershire (Westcountry Books, 1994), p. 3

[iv] http://www.wiltshireheritagecollections.org.uk/wiltshiresites.asp?page=selectedplace&filename=WiltshireSites&mwsquery=%7BPlace%20identity%7D=%7BPreshute%20G1a%7D

[v] Whitlock, Ralph Wiltshire Folklore and Legends (Robert Hale, 1992), p. 24

[vi] Witts, G. B. ‘Description of the Long Barrow called “West Tump,” in the Parish of Brimsfield, Gloucestershire’

Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1880-81, Vol. 5, p. 201-211

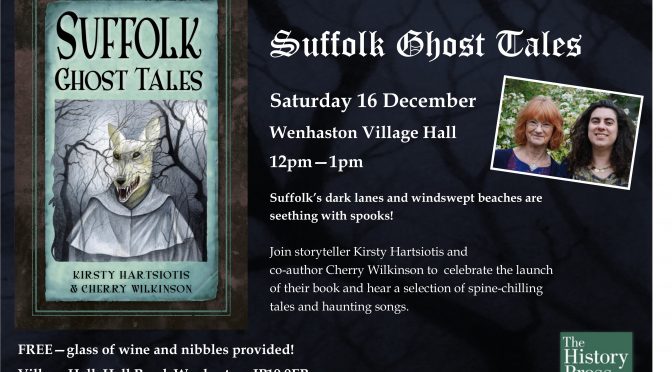

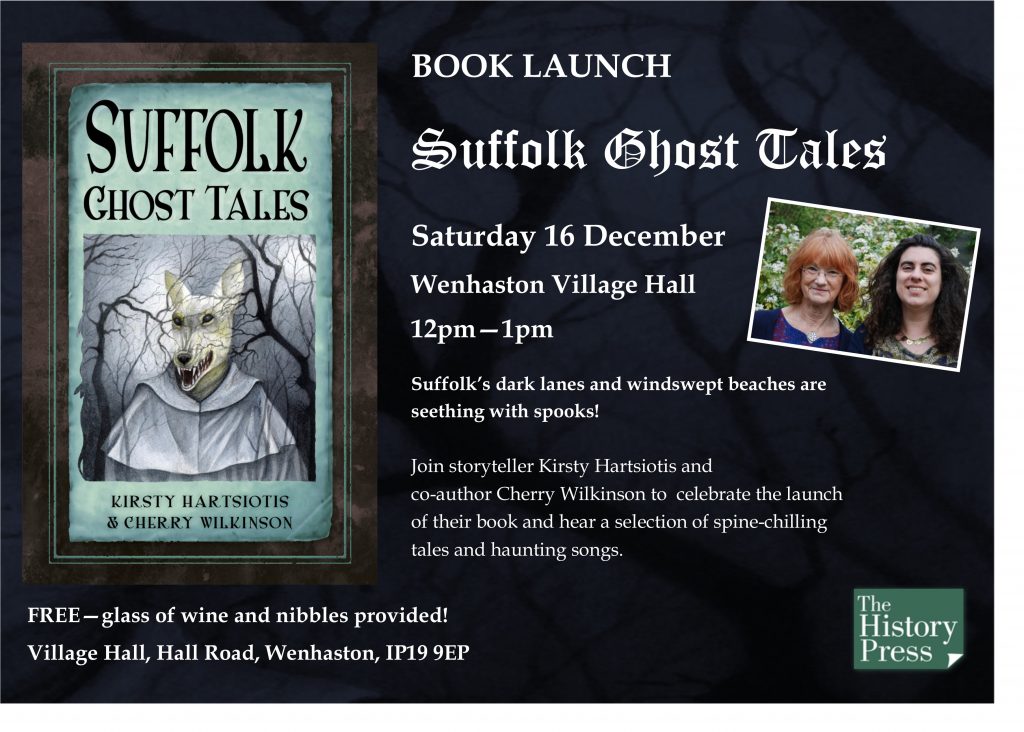

Suffolk Ghost Tales book launch

It’s out! Cherry and I officially launched Suffolk Ghost Tales with a bang on Saturday 16 December in Wenhaston Village Hall – and it was amazing! It felt as if half of East Suffolk came to our book launch party to hear our songs and stories, wish us well, drink fizz and buy the book. The baby’s head has definitely been wetted, and the books are out there now, in the wild…

Here they are before the first sale – alongside a few of my other books! All of the Ghost Tales you see here sold!

Cherry and I planned a whole performance for the event – storytellers and singers don’t like to do things by halves! I told three stories from the book, and Cherry sang three songs associated with the tales. The first of the stories told was especially for a very special Wenhaston lady, Heather Phillips, to whom the book was dedicated. Heather celebrated her 90th birthday this year, and also published her mother’s memoirs in October also at the village hall. When I was researching Suffolk Folk Tales back in 2012, Heather gave us some silly Suffolk stories from the Saints, which went in the book, but also shared some more spooky tales, which I couldn’t fit in. But they were in our minds when we started on the ghost tales. This time we did include them – and one of the tales tells the story of Heather’s great-grandmother … and father. For all her tales and for her unceasing support and interest – Heather even baked a raft of sausage rolls and Suffolk rusks for the event! – we were delighted to present her with a copy of the book and reveal our dedication:

We’re planning a blog about Heather shortly, so watch this space!

Cherry then sang the song Ranter’s Wharf by John Conolly in homage to the story ‘The Constant Maid’ – this was her first public performance in a long time, and she was perfect! I got quite emotional watching her, as I realised that this was the first time that we had ever performed together – not even when she enrolled me in the Young HADS to be the youngest child in The Admirable Crichton, my first acting performance (first line on stage: ‘What are bunions, Nanny?’), as she did the props, not the acting! I’ll be sharing her songs in future blogs…

I then told another tale of love and loss, ‘Kate’s Parlour’, an eerie place on Jay’s Hill near Sotterley – you can see it here:

Next up was a collaboration – Cherry singing ‘The Cat Came Back’ and the true tale of the 1970s adventures of the mummified cat you can see to this day in The Mill Hotel, Sudbury… It came back…

We finished with Cherry singing ‘The Mistletoe Bough’ a typically Christmas song of … being shut in a ‘living tomb’. Ahem. It’s a story that is associated with lots stately homes in England – in Suffolk, it’s Kentwell Hall in Long Melford.

Then the queue formed and we were signing, signing, signing! Thank you everyone who made the event so special – it was a real community event, with Cherry’s friends and neighbours pulling together to help and make it wonderful for us and our audience.

Especially big thank yous go to the following:

Cherry would like to give a special thank you to Helen Rolfe, her music mentor, for the help with the singing.

Jill and Michael and Janice and Roger for all their help setting up- without whom…

David for his sterling work at the drinks stall!

Viv for being our official photographer – we can’t wait for the images!

Dave for everything along the way, but on the day help with drinks and taking the money…

And for baking the treats people had to eat, Heather for sausage rolls and Suffolk rusks, Felicity for onion tarts and Janice for caraway cake – we were told that everything was lovely, but sadly we didn’t get a chance to sample…

Suffolk Ghost Tales for the Dark Nights of Winter

Have a look at this new blog I’ve written for The History Press in advance of Suffolk Ghost Tales coming out on the 13 December about Suffolk’s ghost tales, Suffolk’s most famous ghost story writer, M R James and the tradition of telling ghost stories at Christmas…

‘All places have ghost stories. Laurie Lee, in Cider with Rosie, says, ‘There were ghosts in the stones, in the trees, and the walls, and every field and hill had several.’ He’s talking about Gloucestershire, but, even now, a hundred years on from when Lee was a boy, it still holds true across the country. But of all counties, Suffolk is a little bit special when it comes to ghosts…

The low cliffs, pebble beaches and faded hotels of his home county have become fixed in our minds as subtly dangerous places with a hint of folk horror. All those lost places… Visit Dunwich to see the last grave of All Saints teetering on the edge of the cliff, visit Aldeburgh and see the House in the Clouds bright and distant across the marshes, go to lonely Minsmere and see the ruined chapel, all that remains of a monastery and village abandoned, go to Covehithe … if it’s still there.

Suffolk is, after all, the home county of one of the greatest tellers of ghost tales – M R James. James moved to Suffolk aged three, when his father became rector of Great Livermere, up near the Norfolk border. His family lived there from 1865 until 1909, so James had a foot in Suffolk for much of his life. Several of his tales, ‘Oh, Whistle and I’ll Come to You, my Lad’, ‘A Warning to the Curious’, ‘The Ash-tree’ and more, are set in Suffolk, and develop the disquieting aesthetic we now recognise in the landscape.’

Read the rest of the article here:

https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/suffolk-ghost-tales/

The Secret Disclosed: ghostly riots in Bury St Edmunds

I’m all about ghosts at the moment, what with Suffolk Ghost Tales coming out next week. But this blog is a bit naughty, as it’s actually inspired by the background to a story in my previous Suffolk book, Suffolk Folk Tales. The question is, how do ghosts come to be? You’d think that it would be by someone dying and proceeding to haunt a place, wouldn’t you? But that’s not always the case … sometimes they are conjured up out of the collective mind of the people, and such is the case for the Grey Lady of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk.

Once upon a time there was a woman by the name of Margaretta Greene. She was a scion of the Greene family of Bury, best known, perhaps, for the brewers Greene King. She lived in a very strange building indeed, a building that had once been part of the vast west front of St Edmund’s Abbey, but was – and is – now houses. So vast was the abbey that just one side of the west front contains these houses, organically emerging out the rubble stone that lay beneath the dressed that was all taken away to build other parts of Bury after the monastery was dissolved in 1539. The Marquis of Bristol, who owned the abbey land from 1806, had the west front converted into houses, as well as beginning the Abbey Gardens we know today. They were nearly destroyed in the 1950s, but fortunately are still with us today.

These houses lie close to the Great Churchyard between the abbey and St Mary’s, and it’s easy to imagine the affect this setting might have on a Romantic young woman… In 1861 she privately published a slender volume entitled The Secret Disclosed: A Legend of St Edmund’s Abbey ‘by an Inmate’ telling a sorrowful tale of unrequited love, royal conspiracies, murder, poison, and death in the secret tunnels that were said to lie under the town connecting its religious buildings. The protagonist of this tale, young nun Maude Carew and Queen Margaret of Anjou, the definite baddie in this melodrama, she said, haunted the Churchyard every 24 February at precisely 11pm.

The people of Bury fell for it hook, line and sinker. Well, why wouldn’t they? Margaretta had said that she’d heard footsteps in her house, which had led her to find a casket containing the manuscript which she had simply transcribed … well, it had to be true, didn’t it?

The next 24 February, 1862, a horde of folk gathered in the Churchyard to see the ghosts. Did people really expect to see a ghost? It seems so, as by the time 11pm approached, the crowd was so excited as to be almost hysterical. And when, inevitably, the ghost didn’t appear? Well, some said that it did – but no one could agree on what the ghosts looked like. Were they white? Were they black? The mood turned ugly as the crowd realised they’d been duped. All hell broke loose, the ghost watchers rioted – and indeed a window was broken in Greene’s house.

And yet, Maude Carew, despite being a fictional character, lived on as a ghost in Bury. She became the Grey Lady of Bury, taking over the personalities of other Grey Ladies in the town and roving way beyond her proper haunting ground of the west front and churchyard. Can she possibly be the female ghost who is said to haunt Cupola House in the Traverse, along with the object of her desire, Father Bernard – aka the brown monk? More realistically, a Grey Lady, dressed in the robes of a nun, is said to haunt the Fornham Road area, including St Saviour’s hospital. Now, this isn’t unreasonable, if the story Greene was true, as it was at St Saviour’s hospital that the unfortunate victim in the story, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, died that 24 February 1447.

Yes, the tale does have a historic background – one familiar to both students of history and students of literature, as his tale is immortalised in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part II. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester was Henry VI’s uncle, and was Lord Protector, and, after 1435, was heir to the throne. In 1441 his wife, Eleanor, was arrested on a charge of witchcraft, for, with ‘the Witch of Eye’ (no, not the Suffolk Eye, ‘Eye next Westminster’) Margery Jourdemayne, it was prophesised that Henry VI would die that year. Of course, he did not, and this was the end of Humphrey’s career – and Eleanor and Margery’s lives. He was summoned to a parliament at Bury in 1447. There was a rumour Humphrey was poisoned, but he might also have had a stroke, as he lay unconscious for three days after a banquet. If he was poisoned, it’s just as likely that it was by the Earl of Suffolk, William de la Pole, as it was thought that Suffolk’s enemies might rally to Gloucester… And that is what was whispered during Cade’s rebellion in 1450 that saw Suffolk fall from grace, although there is no evidence that he was poisoned. Dark, complicated times – I think we can identify with them!

This story has been taken from Haunted Bury St Edmunds by Alan Murdie (Tempus, 2006). Murdie is a great expert on Bury’s ghosts – and is also the Chairman of the Ghost Club. I fell in love with the tale when I first read it, researching Suffolk Folk Tales back in 2012, and think it sad that A Secret Disclosed isn’t available … anywhere! Not even on archive.org. There is a copy in the Record Office in Ipswich – but what other copies exist? It would be a shame for the ghost to live on, but the original story to die…

Images:

The images of the churchyard and west front are copyright Kirsty Hartsiotis, 2017

Copyright info for the image of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester can be found here.

Suffolk Ghost Tales – launch party!

Ooh, the launch of Suffolk Ghost Tales is coming up very fast now! We’re officially launching the book in Cherry’s home village, Wenhaston, near Southwold, on the 16 December – just three days after the book comes (nail-biting stuff!!), so it will be Christmas come early for us! The event’s at 12pm in the Village Hall, and is turning into a real village effort, with help and, most importantly, food being given by Cherry’s friends. There’ll even be proper Suffolk rusks to go with the fizz! And it’s free – although of course there will be copies of the book to tempt – as well as Suffolk Folk Tales and my other books!

I’ll be telling ghostly tales from the book – some local to the Wenhaston area, some not, and Cherry will be singing ghostly songs that relate to the stories and bringing us around to Christmas … that prime ghost story time.

It will be very special to perform alongside her! Cherry, of course, being the person who got me interested in all things folk in the first place. You can find out about how she introduced me to Suffolk’s most famous folk tale, the Green Children, here. Maybe I wasn’t so keen when she and my stepdad dragged me along to folk clubs and festivals as a child, but by the time I was in my early teens I was hooked. I became a storyteller because I couldn’t do what she could – sing – and wanted a way to share the stories I loved. And now we can perform together!

Come and join us if you can – and if not, you can buy the book here. There will be lots more blogs discussing our journey in researching the stories, and discussing the histories behind them here on Palace of Memory, and more events in Suffolk in the New Year – watch this space!

Suffolk Ghost Tales – out very soon!

Very exciting news! My new book is out in just a few weeks on the 13 December – Suffolk Ghost Tales, part of The History Press’s ghost tales series. This time, it’s been a really special collaboration – with my mother, Cherry Wilkinson.

Very exciting news! My new book is out in just a few weeks on the 13 December – Suffolk Ghost Tales, part of The History Press’s ghost tales series. This time, it’s been a really special collaboration – with my mother, Cherry Wilkinson.

Here’s the blurb:

SUFFOLK – a peaceful, rural county with big skies, rolling fields, unspoilt beaches, quaint towns and villages. But all is not as quiet as it seems. Could that be the eerie clanking of gibbet chains at the crossroads? Did you see a desolate face at an upper window or a spectral white form lurking in the hedgerow? Cats are not always lucky – and beware a north Suffolk Broad in the still, small hours of Midsummer Night . . .

Kirsty Hartsiotis and Cherry Wilkinson retell, with spine-chilling freshness, thirty fabulous ghost tales from all corners of this beguiling county. So pull up a chair, stoke the fire and prepare to see its gentle landscape in a new light.

Cherry and I moved to Suffolk when I was two, living first near Hadleigh, later in Bury (and a couple of stints over the border in Norfolk, shh). I left, but Cherry still lives in the county, near the coast. Her association goes back long before I was born: her great-aunts who lived in the house next to Lindsey’s little chapel, and through school at St Felix, Southwold and holidays at Sizewell before the power station changed everything… We had a chance to dig more deeply into Suffolk’s heritage a few years ago when I wrote Suffolk Folk Tales (The History Press, 2013).

But there were many places we realised we’d never seen – well, this book has gone a long way to rectifying that. It’s been quite a ride, discovering these wonderful, spooky – often sad, sometimes hair-raising! – stories and working together to create the tales we’ve told. Some you might know well – there’s the story of Toby, the black drummer, and the sad tale of the Lowestoft witches. We’ve travelled all over the county visiting the locations of the tales, talking to the current owners of buildings, and discovering some new stories from people we know.

Suffolk is the ghost county – childhood home of M R James, and the setting for some of his scariest tales. Katherine Soutar‘s wonderful cover illustration hooks into that unheimlich world on the edge of our own… Our tales tread a point somewhere between storytellers’ local legends and the literary ghost story. We hope you will share these stories, too, and keep the tales of the dead alive.

We’re celebrating with a launch event in Wenhaston Village Hall, near Southwold, on the 16 December 12pm. Come and hear tales and songs, and celebrate with a glass of wine!

On Downham Hill … a fairy story for Halloween

It’s the ghost month, October. The month of Halloween and Samhain, when, once again, the veil is thin between this world and the Otherworld of the fairies and the dead. The nights are drawing firmly now, too – at the end of the month, we’ll be changing the clocks and suddenly the evenings will be short. It’s a month for storytelling, for telling tales of that Otherworld. I’ve got a number of gigs coming up in the next few weeks to do just that, and to reveal the hidden places where you might find … something else …

Here’s the science bit: I’m with Anthony at The Wilson in Cheltenham on the 26 Oct, in Stinchcombe Village Hall on my ownsome todd on the 27 Oct, and this Friday 13 I’m in Newent with Anthony, Val Dean and Austin Keenan at the Secret Gallery – more details at the bottom!

One of the tales I’ll be telling is a tale from very close to where we live in Stroud, On Downham Hill, which concerns a certain inn that you might – if you were lucky, if you were unlucky – find up there on a bleak night… I see it a lot, as our cat’s cattery is at the bottom of it! I confess I’ve only been up there once, but fittingly, it was in the snow… Downham Hill is one of the range of hills that lie close to the village of Uley, south of Stroud, north of Dursley. It sits by itself just southwest of Uley Bury with a stand of trees on its flat summit.

This is a storied area. From Downham Hill you can easily see the next hill west, Cam Peak, whose pointed tip derives from the fact that the Devil dumped it there when he was on his way to dam the Severn (because there was, of course, too much God in Gloucestershire), and was foiled by meeting a cobbler with a full pack of worn out shoes to fix. Asked by the Devil how far it was to the river, the cobbler thought fast and told the Devil it was a long, long way – he’d worn out all those shoes just coming from there…

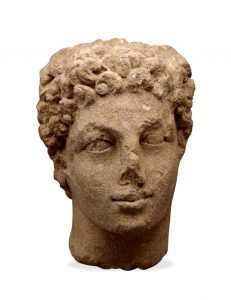

There’s a pair of silver gates buried up on Crawley Hill, somewhere – something to search for on the long roll down to Uley from Stroud. It might be by Money Quarr on West Hill – the site of a Roman complex, including a temple to Mercury[1]. In this case, then, the idea that there might be treasure has been borne out by the finds of statuary – including this head of the cult statue of Mercury – coins, curse tablets and more. But silver gates? Just keep looking, folks!

There’s a pair of silver gates buried up on Crawley Hill, somewhere – something to search for on the long roll down to Uley from Stroud. It might be by Money Quarr on West Hill – the site of a Roman complex, including a temple to Mercury[1]. In this case, then, the idea that there might be treasure has been borne out by the finds of statuary – including this head of the cult statue of Mercury – coins, curse tablets and more. But silver gates? Just keep looking, folks!

And is Cam Long Down actually Camlann, where Arthur and his son, Mordred, fell..?

Downham Hill, however, is a place of fairies. There may be other records of the fey in Uley – was Fiery Lane, the road from Uley down to Owlpen, once Fairy Lane? Roy Palmer suggests so.[2] But Downham Hill, somewhat isolated despite the farms that ring its base, has the reputation of being a place you wouldn’t want to travel to alone. Just the place to find the trickery of the fairies that our protagonist encounters, you might think.

But there’s another explanation for why the villagers kept away. Downham Hill was chosen in the 18th century as the site of a smallpox hospital. It was, apparently, one of the earliest ones, and may have had a link with Dr Jenner, who discovered the vaccination for the disease, and who lived at nearby Berkeley. If it was an isolation hospital, then no wonder the villagers were suspicious – and the hill got the nickname ‘Smallpox Hill’. Added to that is that on the top of the hill is further remains of an older tower-like cottage put up during the reign of Edward III – at around the time of the Black Death[3]. It really is a plaguey hill. Mind you, all the websites are rather vague about both the monument and the hospital, so maybe it’s the fairies after all, warning all us folks away!

Fairy inns are known up and down Britain, and fall into the tale type to do with fairy gifts. Another tale being told on Friday 13th is that of the fairy ointment, where a midwife gets an inadvertent gift from the fairies … until they discover she has it. This tale too shows that the fairies like to give with one hand and take away with the other – as all Harry Potter fans know leprechaun gold turns to leaves after a little time. Probably the best you’re going to get out of it is for everything to stay as it was – but there is a little tale not that far from Uley, from the Wickwar and Wotton-under-Edge area of a ploughman who hears a small, shrill lamentation from by his feet, and when he looks down he sees a tiny little peel (the wooden shovel that bakers (and pizza makers!) use) snapped in two in the dirt. Very carefully, the ploughman picked up the pieces and took it home. That night, he managed to fix it, and the same he took it back and put it where he found it. Later, smelling baking, he followed the smell, and there, in the furrow was left a tiny plum cake – which he ate![4] But perhaps the traveller on Downham Hill was luckier … he got away with his life.

If you’d like to hear this and other stories of the season, here are the gigs:

Friday 13 October Storytelling Evening at the Secret Gallery, Newent, 7pm

Images:

- Downham Hill © Copyright Philip Halling and licensed for reuse under creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0

2. Head from a statue of Mercury, 1978,0102.1, AN33834001 © The British Museum

Notes:

1] http://curses.csad.ox.ac.uk/sites/uley-home.shtml

[2] Palmer, Roy The Folklore of Gloucestershire (Westcountry Books, 1994), p. 49

[3] http://cwr.naturalengland.org.uk/default.aspx?Site=5939

[4] Palmer, p. 141