Lately, I’ve been intrigued by the different ghosts that emerge from the many, many prehistoric barrow mounds in the west. I’m doing talks on Gloucestershire’s ghosts and Wiltshire’s folklore, and I’ve been reminded of how, here in the west, they form an important part of the folklore of the region. This blog, probably the first of a few, explores some of the hauntings and their tales – if you’d like the full tales, you’ll find some of them in my books Wiltshire Folk Tales and Gloucestershire Ghost Tales.

Ghosts, fairies or giants? The case of Hackpen Hill

Back in antiquarian John Aubrey’s time, the 17th century, the mounds and the downland on which they were situated were things to be feared. In the long barrows, giant’s bones resided, and the very ground could open up and take you – like these incidents on Hackpen Hill near Avebury:

‘Some were led away by the Fairies, as was a Hind riding upon Hakpen with corne, led a dance to the Devises. So was a shepherd of Mr. Brown, of Winterburn-Basset: but never any afterwards enjoy themselves. He sayd that the ground opened, and he was brought into strange places underground, where they used musicall Instruments, violls, and Lutes, such (he sayd) as Mr. Thomas did play on.’[i]

Aubrey collected these snippets in his collection Remaines of Gentilisme and Judaisme, of 1686-7 – but not published until 1881 by the Folklore Society. It is a collection of folklore from all over Europe, collected together willy-nilly, with a little local lore slotted in. Aubrey recorded that the people in the area thought that the long barrows around were the graves of giants. Round barrows were easily recognised as graves, too. Aubrey records that on Hackpen Hill ‘in a barrow … after digging, was found at thigh-bone of a man and several urns’. Many people at that time believed that what they were finding were the remains of Saxons and Vikings in these mounds. In some cases, of course, this was true – also on Hackpen Hill in the late 19th century Canon Greenwell, ‘a prolific excavator of barrows’, found evidence of the reuse of a Bronze Age barrow, finding a later Saxon inhumation with an iron spear over a cremation burial with a bronze dagger[ii]. Aubrey and his contemporaries were hindered by the lack of knowledge that there had been earlier cultures in Britain than that of the Iron Age that the Romans encountered and wrote about. Geoffrey of Monmouth explains away Stonehenge by ascribing it to Merlin’s magic (and giants in Africa … but that’s another story) but Aubrey and his contemporaries realised it and the other standing stones and burial mounds were much earlier, his generation creating a long-lasting misconception about druids and stone circles that still continues in the national psyche.

The haunting of the Woeful Dane

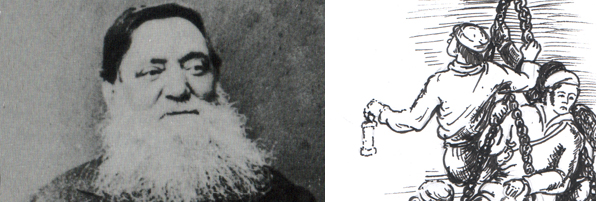

The idea, though, that it was Saxons and Vikings in the mounds lingers… In Gloucestershire, one of my out and out favourite stories is that of Molly the Dreamer of Minchinhampton, who encounters the ‘Woeful Dane’ (actually a Saxon) who is said to have named Woefuldane’s Bottom near the Long Stone. He was Wolfhang, and his shade haunts the lane. To Molly, though, he promised aid in the form of the glittering gold hidden in his grave – I won’t tell the tale, it’s in Gloucestershire Ghost Tales – but suffice to say that she didn’t get it! Sadly, the great battle where the Saxons under Wolfhang routed the Danes exists only in the imagination of the people of Minch – the name Woefuldane probably derives from a place where a wolf was caught[iii] … although that might shed some light on the see-through, headless black dog that also haunts the lane, and who caused carters in the 19th century to insist on being blindfolded on that stretch of road at night, lest they see its insubstantial form. Gatcombe Tump, Wolfhang’s mound, is a Cotswold-Severn type long barrow – dating from the early Neolithic, about 3500BC.

‘She did come out of the mound’

In the story at Manton barrow, near Marlborough, the tale goes that a finger bone was borrowed by a journalist after the excavation in the early 20th century, and when taken to a séance, a wronged Saxon princess was conjured up by the medium! Manton barrow is a round barrow in which were found the remains of ‘a woman of considerable age, and that their period was somewhere during the latter portion of the Bronze Age.’[iv] But there is a coda that seems more real. The grave goods were taken to Devizes Museum, but the skeleton was returned to the grave. Soon after, a woman of the village complaining to her doctor: ‘every night since that man from Devizes came and disturbed the old creature she did come out of the mound and walk around the house and squinny into the window. I do hear her most nights and want you to give me sammat to keep her away.’[v] Alcohol is secretly prescribed, and the old woman sleeps soundly from then on but I feel sorry for the lonely ‘old creature’, perhaps only seeking companionship after her lonely grave was disturbed and her spirit released.

‘I suddenly saw before me a long barrow’

The idea that the spirits of the dead are disturbed by excavation can also be seen in the tales of ghosts around the hard to find West Tump. Another Cotswold-Severn long barrow, it was discovered by the well-known Gloucestershire archaeologist, G B Witts, by accident while on a Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society outing in 1880. Witts, on horseback as opposed to in a carriage, took a shortcut through Buckholt Woods, and as he was riding through the portion the OS map calls Buckle Wood, with, as he says, ‘my mind intent on archaeology, and I suddenly saw before me a large barrow!’[vi] The barrow was duly excavated, the innumerable human remains removed in this case to the museum at Cheltenham, and, in time, nature covered the mound once more. But the people knew that the spirits were restless, and figures began to be seen around the mound, figures in leather cloaks, inked with tattoos and bearing stone-tipped spears. The ghosts in these last two stories, both from an era when people knew more about the pre-history of Britain, are more up to date, the ghosts seemingly reflecting the real occupants – or at least people’s imagined ideas of them.

It seems we create our ghosts anew with every generation, assimilating new information. What ghosts do the mounds conjure a hundred years on from the excavation of Manton Barrow? The mounds are now more in use than ever, visited by walkers and the curious – and by modern pagans honouring the ancestors and reinventing and imagining what might have happened when the original dead were laid to rest. But we know not what expectations the makers of the mounds had. Did they expect the spirits of their ancestors to lie quietly, as we expect of the dead today, or did they envisage a more active role for the spirits, perhaps, in the Bronze Age at least, still working to protect the living – many round barrows are placed on hills and ridges, or on boundaries. Were they set there to guard the land and the people in some way? What then if the barrow is disturbed? We can imagine that there would be dire consequences in the stories of the folk who raised the mounds… Did those stories linger? Perhaps it’s no wonder that the idea of ghosts – or fairies – in the mounds has come down over the centuries even to our materialist age.

Images:

- Featured image: Gatcombe Tump, near Minchinhampton © Kirsty Hartsiotis, 2014

- A view of Hackpen Hill, near Winterbourne Bassett

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Brian Robert Marshall – geograph.org.uk/p/1010217 - Wolfhang © Kirsty Hartsiotis, 2015

- The ‘Old Creature’ © Kirsty Hartsiotis, 2011

- West Tump ( Long Barrow )

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Michael Murray – geograph.org.uk/p/937490

References:

[i] Britton, John, ed. The Remaines of Gentilisme and Judaisme by John Aubrey RSS 1686-87 (The Folklore Society, 1881), p. 30

[ii] http://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/4598/hackpen_hill_wiltshire.html

[iii] Palmer, Roy The Folklore of Gloucestershire (Westcountry Books, 1994), p. 3

[iv] http://www.wiltshireheritagecollections.org.uk/wiltshiresites.asp?page=selectedplace&filename=WiltshireSites&mwsquery=%7BPlace%20identity%7D=%7BPreshute%20G1a%7D

[v] Whitlock, Ralph Wiltshire Folklore and Legends (Robert Hale, 1992), p. 24

[vi] Witts, G. B. ‘Description of the Long Barrow called “West Tump,” in the Parish of Brimsfield, Gloucestershire’

Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1880-81, Vol. 5, p. 201-211