I’m all about ghosts at the moment, what with Suffolk Ghost Tales coming out next week. But this blog is a bit naughty, as it’s actually inspired by the background to a story in my previous Suffolk book, Suffolk Folk Tales. The question is, how do ghosts come to be? You’d think that it would be by someone dying and proceeding to haunt a place, wouldn’t you? But that’s not always the case … sometimes they are conjured up out of the collective mind of the people, and such is the case for the Grey Lady of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk.

Once upon a time there was a woman by the name of Margaretta Greene. She was a scion of the Greene family of Bury, best known, perhaps, for the brewers Greene King. She lived in a very strange building indeed, a building that had once been part of the vast west front of St Edmund’s Abbey, but was – and is – now houses. So vast was the abbey that just one side of the west front contains these houses, organically emerging out the rubble stone that lay beneath the dressed that was all taken away to build other parts of Bury after the monastery was dissolved in 1539. The Marquis of Bristol, who owned the abbey land from 1806, had the west front converted into houses, as well as beginning the Abbey Gardens we know today. They were nearly destroyed in the 1950s, but fortunately are still with us today.

These houses lie close to the Great Churchyard between the abbey and St Mary’s, and it’s easy to imagine the affect this setting might have on a Romantic young woman… In 1861 she privately published a slender volume entitled The Secret Disclosed: A Legend of St Edmund’s Abbey ‘by an Inmate’ telling a sorrowful tale of unrequited love, royal conspiracies, murder, poison, and death in the secret tunnels that were said to lie under the town connecting its religious buildings. The protagonist of this tale, young nun Maude Carew and Queen Margaret of Anjou, the definite baddie in this melodrama, she said, haunted the Churchyard every 24 February at precisely 11pm.

The people of Bury fell for it hook, line and sinker. Well, why wouldn’t they? Margaretta had said that she’d heard footsteps in her house, which had led her to find a casket containing the manuscript which she had simply transcribed … well, it had to be true, didn’t it?

The next 24 February, 1862, a horde of folk gathered in the Churchyard to see the ghosts. Did people really expect to see a ghost? It seems so, as by the time 11pm approached, the crowd was so excited as to be almost hysterical. And when, inevitably, the ghost didn’t appear? Well, some said that it did – but no one could agree on what the ghosts looked like. Were they white? Were they black? The mood turned ugly as the crowd realised they’d been duped. All hell broke loose, the ghost watchers rioted – and indeed a window was broken in Greene’s house.

And yet, Maude Carew, despite being a fictional character, lived on as a ghost in Bury. She became the Grey Lady of Bury, taking over the personalities of other Grey Ladies in the town and roving way beyond her proper haunting ground of the west front and churchyard. Can she possibly be the female ghost who is said to haunt Cupola House in the Traverse, along with the object of her desire, Father Bernard – aka the brown monk? More realistically, a Grey Lady, dressed in the robes of a nun, is said to haunt the Fornham Road area, including St Saviour’s hospital. Now, this isn’t unreasonable, if the story Greene was true, as it was at St Saviour’s hospital that the unfortunate victim in the story, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, died that 24 February 1447.

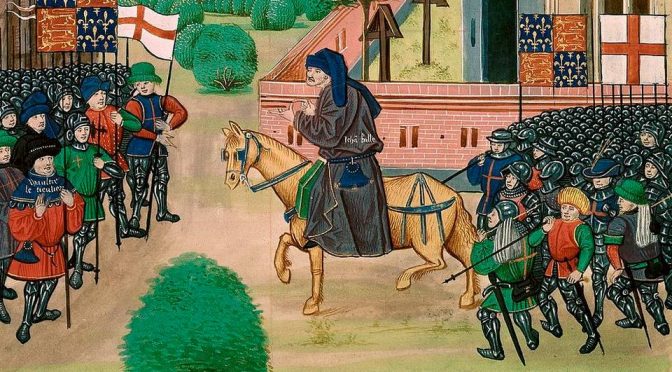

Yes, the tale does have a historic background – one familiar to both students of history and students of literature, as his tale is immortalised in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part II. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester was Henry VI’s uncle, and was Lord Protector, and, after 1435, was heir to the throne. In 1441 his wife, Eleanor, was arrested on a charge of witchcraft, for, with ‘the Witch of Eye’ (no, not the Suffolk Eye, ‘Eye next Westminster’) Margery Jourdemayne, it was prophesised that Henry VI would die that year. Of course, he did not, and this was the end of Humphrey’s career – and Eleanor and Margery’s lives. He was summoned to a parliament at Bury in 1447. There was a rumour Humphrey was poisoned, but he might also have had a stroke, as he lay unconscious for three days after a banquet. If he was poisoned, it’s just as likely that it was by the Earl of Suffolk, William de la Pole, as it was thought that Suffolk’s enemies might rally to Gloucester… And that is what was whispered during Cade’s rebellion in 1450 that saw Suffolk fall from grace, although there is no evidence that he was poisoned. Dark, complicated times – I think we can identify with them!

This story has been taken from Haunted Bury St Edmunds by Alan Murdie (Tempus, 2006). Murdie is a great expert on Bury’s ghosts – and is also the Chairman of the Ghost Club. I fell in love with the tale when I first read it, researching Suffolk Folk Tales back in 2012, and think it sad that A Secret Disclosed isn’t available … anywhere! Not even on archive.org. There is a copy in the Record Office in Ipswich – but what other copies exist? It would be a shame for the ghost to live on, but the original story to die…

Images:

The images of the churchyard and west front are copyright Kirsty Hartsiotis, 2017

Copyright info for the image of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester can be found here.