I’m telling stories about ancient technology at Gloucester History Festival on Saturday, and flying machines do come into it…

People have always wanted to fly. The stories of the gods and goddesses of the world imagine our earthbound chariots and horses into the air – think of Helios’s sun chariot, or Freya’s chariot pulled by cats. Bellophron rides Pegasus, a flying horse born of Poseidon and Medusa. The Egyptian god Horus was a falcon-god. In the Ramayana, gods and demons have vimanas, chariots powered by the air.

Daedalus and Bladud

The most famous story is, of course, that of Daedalus and Icarus. The great Greek inventor, trapped on Crete with his son, devised wings made of feathers, string and wax, and flew safely to Naples, where he dedicated his wings to Apollo – something we often forget when thinking of how Icarus fell to his death. There was nothing wrong with Daedalus’s wings! You just had to use them safely, as with any dangerous tool. Inspired by this, King Bladud of Britain, who had studied in Athens in his youth, built himself a pair of wings through his studies in necromancy (did he channel the spirit of Daedalus?) and flew from the temple of Apollo in London – but like Icarus, he fell, and died.

Alexander the Great

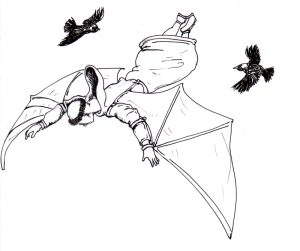

More successful early flights include that of Alexander the Great. In the Alexander Romance, which first appears about the 3rd century AD, Alexander has a number of strange adventures: he travels down to the bottom of the ocean in a diving bell; he defeats the barbarians of the north giants Gog and Magog, and, ahem, builds a wall[i] to keep them out; his sister is turned into a mermaid. But he also flies. His flying machine is fairly basic – he goes up in a glass-bottomed chariot drawn by griffins chasing either jewels or meat held perpetually out of their grasp. Alexander goes further than Daedalus or Bladud – he travels so far into space that he can see the whole world, likened to a coiled snake, satisfying his desire to see the ends of the earth – and not learning the lesson of Scipio Aemilianus, the destroyer of Carthage, from Cicero’s On the Republic. Scipio dreams of flight, and is shown ‘how small the earth appears in view of heaven’s own immensity’, thus learning humility and showing how the mind should kept on spiritual, not earthly matters.

Icarus … again?

The satirical writer Lucien took to the skies twice in his writing. Firstly, the well-known journey to the moon in his ‘True History’, in which the protagonists are shot into the air in their ship by a water spout. Less well-known is the story of Icaromenippus, who, like Daedalus, builds wings and flies to Mount Olympus – where he discovers that Zeus is planning to king all philosophers for being useless – or at least will get round to it after the long vacation! Menippus feasts with the gods (and in true Roman fashion, is placed with the least favoured gods on the bottom table…) and sneaks a taste of ambrosia and nectar, but is deprived of his wings and set back down on the earth again by Hermes.[ii]

Eilmer, a Wiltshire aviator!

Daedalus was also the inspiration to the first non-legendary flight in Britain, that of Eilmer of Malmesbury, the story of which features in my book, Wiltshire Folk Tales. Eilmer was a monk at Malmesbury Abbey, much later than all these classical fantasies, and was known to the writer of his story, William of Malmesbury. The story is told in his Deeds of the English Kings of 1125. Eilmer only died in 1066, and so there would have monks at the abbey who would have remembered Eilmer when William first joined the monastery as a boy in the late 11th century.

As a historian, William is surprisingly well-respected – one of my favourite accounts of his is of the witch of Berkeley, a rather fantastical tale, which he preambles with the following:

At the same time something similar occurred in England, not by divine miracle, but by infernal craft; which when I shall have related, the credit of the narrative will not be shaken, though the minds of the hearers should be incredulous; for I have heard it from a man of such character, who swore he had seen it, that I should blush to disbelieve.[iii]

This is careful distancing! So why not a flying monk? William states that he was inspired by reading a book on Daedalus, and was inspired to build a pair of wings. William also says that he flew for more than a furlong – more than 200 metres – before the twin problems of the wind and his own realisation of what he was doing caused him crash. Powered flight it isn’t – but nonetheless, Eilmer flew – find out more about him and his experiences with Halley’s Comet in my Wiltshire Folk Tales.

He was the first in Britain, only following three other accounts of tower jumping, one in China in the 1st century AD, one in the 6th, and one in Spain in the 9th. The first Chinese jumper glided 100 metres – so Eilmer’s glide was twice as long. The Chinese seem to have experimented with man-carrying kites, as well, and possibly the Japanese, too.

It wasn’t until the 18th century that flight took off, as it were, first with balloons, and the rest was history!

Cats?

A cat flew in 1648. The Italian inventor Tito Livio Burattini built a model winged ‘dragon volant’ … at least he knew the passenger would always land on their feet…[iv]

When researching Heron of Alexandria, however, I discovered the earlier inventor, Archytas, from Tarentum in southern Italy. Archytas created a flying creature – a pigeon, powered by steam! See the excellent Kotsanas Museum for more: http://kotsanas.com/gb/exh.php?exhibit=2001001

Notes:

[i] Trump might well be inspired by Alexander, a fellow narcissist. It’s not just the wall – consider Alexander’s bouffant blond locks and, er, Trump’s…

[ii] ICAROMENIPPUS, AN AERIAL EXPEDITION, http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/luc/wl3/wl309.htm

[iii] William of Malmesbury, The History of the Kings of England and the Modern History of William of Malmesbury (Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, 1815), p. 264

[iv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_flying_machines

Images:

1: John Peter Gowy The Flight of Icarus, 1635-7. The Prado, Madrid.

2. Illustration from Le Livre et le vraye hystoire du bon roy Alixandre, French, c. 1420, BL Royal 20 B XX

3. Eilmer copyright Kirsty Hartsiotis, 2011