When Alfred Linnell set out to see what was going on at the protest in Trafalgar Square he can have had no idea what was going to happen. He might have expected some violence – after all, the previous Sunday had been pretty vicious, but the day was getting on and he was only going for a look. Once there, he saw that the mounted police were there before him, riding, it seemed, without a thought for the humans through whom they plunged. As they came closer to him, he added his voice to those shouting at them. The mounted police dove towards those shouting, while the police on foot started to drive the people away. People panicked and fled, Linnell among them. A charger knocked him down, and as he lay there looking up at the huge beast, it trampled him down, smashing his thigh. He was left there to lie in agony, even though there was a police ambulance nearby. Bystanders took him to the hospital at Charing Cross. Twelve days later he was dead.

The 20 November 1887 isn’t the more famous of the two Sundays in November when protesters took to the streets around Trafalgar Square. The previous Sunday, the 13th, 129 years ago to this day, has gone down in history as the first ‘Bloody Sunday’. Many were injured. Three died. But it was Linnell, a seemingly innocent bystander only lately arrived at the protest scene, who became the martyr for the cause. His death became a rallying point for the socialists and anarchists in London to join with the ordinary people and to mark a dark day in the way the police were allowed to treat people, how the law ran roughshod – literally – across the demands of those ordinary people. People who were still, in the main, disenfranchised and with few of the rights we take for granted today. Linnell’s death was a small stepping stone in raising public awareness to social injustice in the Victorian world.

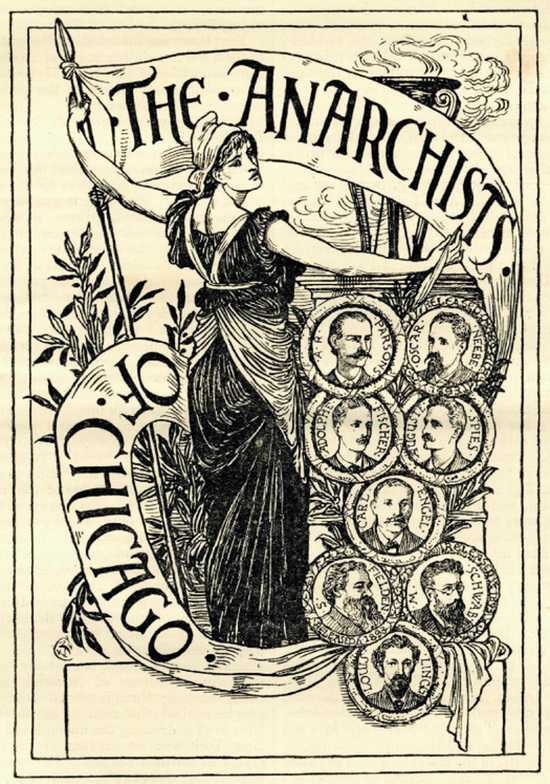

Bloody Sunday came only two days after the execution of the four Chicago Anarchists. Their deaths acted as an impetus to galvanise the various groups of socialists and anarchists in London to protest – and there was a readymade protest group just sitting there in London waiting for them. The 1880s were the hard times in old England – the country was deep in the ‘long depression’, and there was mass employment. Many people came to London, but found the streets were not paved with gold. Only greater hardship awaited them – no benefits of any kind then, of course. Trafalgar Square had become a gathering place for the unemployed, giving speeches, organising themselves… But it wasn’t just them. There were supporters of Irish Home Rule protesting there as well, against the Coercion Acts. On 8 November protests were outlawed. This also galvanised the socialists, the anarchists, the radicals, who not only supported workers’ rights but also, critically, the right to free assembly and speech.

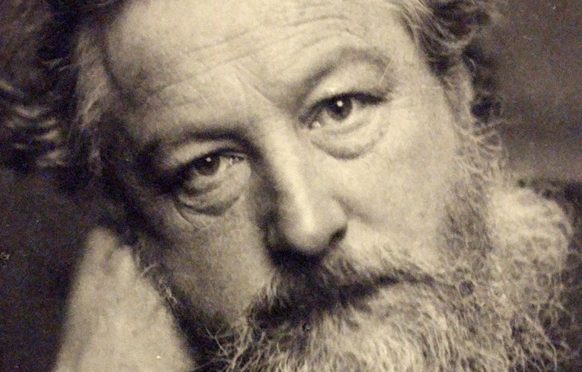

On Sunday 13 November more than 10,000 protestors marched towards Trafalgar Square. Estimates say that there were 30,000 people there that day. Waiting for them in the Square were up to 4000 police and troops – those latter armed. The protesters were marching into a trap. William Morris said afterwards ‘into the net we marched’[i]. Marching from Clerkenwell was the Socialist League, including Morris, Annie Besant, Eleanor Marx and others. There were speeches, there was a band playing. But it didn’t last.

Morris was walking in the middle of the crowd with Fabian playwright George Bernard Shaw, and, through some sixth sense, guessed there was trouble ahead. Pushing to the front he saw the police were there. Their banner was torn out of the hands of Mrs Taylor, despite her determination to keep it[ii], and the band’s instruments smashed.[iii] The police didn’t care if you were a man or a woman. They actually got hold of Eleanor Marx, but she managed to escape with only a whack from a truncheon and a blow to the head…[iv] Morris, in the thick of the action, said, ‘I shall never forget how quickly these unarmed crowds were dispersed into clouds of dust…’[v] Many of the protestors lost their nerve. Shaw says, ‘Running hardly expresses out collective action. We skedaddled … I think it was the most abjectly disgraceful defeat ever suffered by a band of heroes outnumbering their foes a thousand to one.’[vi] Morris didn’t run, but his words give a sense of his fear in that moment, ‘I found myself suddenly alone … and, deserted as I was, I had to use all my strength to get to safety.’[vii]

Morris pressed on, reaching the Square, where he found the police and troops in control. It was a rout. That night, the police sang Rule Britannia and shouted out ‘Hurrah’ all night. The Times reacted to the protest, saying, ‘It was … no serious conviction of any kind, and no honest purpose that animated these howling toughs. It was simple love of disorder’. It described the protestors as ‘howling roughs’ and ‘criminals’.[viii] Those who were there told a different story. Walter Crane said ‘I never saw anything more like real warfare in my life – only the attack was all on one side.’[ix]

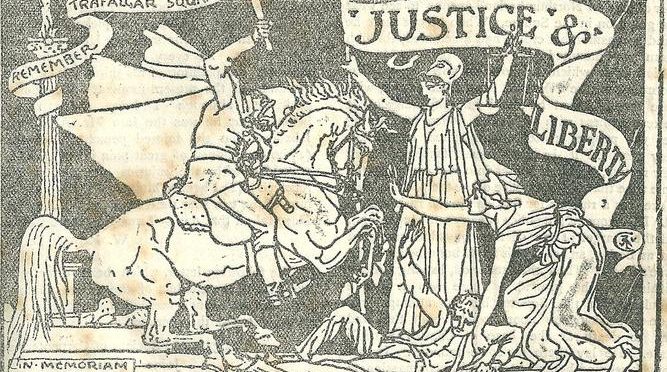

When Linnell died the following week Crane and Morris came together to create a pamphlet to help raise money for his orphaned children. They were already in the workhouse. Linnell was poor, copying law documents for a very bare living, and when his wife had died he couldn’t keep the family together. The girl was in Mitcham, the boy, Harwich. Nobody even told them that their father was sick. What happened to them afterwards isn’t known. Did the pamphlet help? It includes a cover image by Crane and a poem by Morris set to music by Malcolm Laswson, and an account of Linnell’s life and death.

Linnell was given a grand funeral. A huge procession walked from the West End of London to the East, swelling to tens of thousands. On that drizzly December 18, it was dusk by the time they reached Bow Cemetery. Speeches were read by lamplight. Morris gave an emotional eulogy, including the words, ‘let us feel he is our brother’, and his Death Song was sung.[x] The verse at the top is from Morris’s poem.

This bald account of those three dramatic days may serve as a reminder of how hard the fight was to gain what we have today. The Chicago Anarchists, perhaps, went into the fight with their eyes open as to the danger. But Alfred Linnell? His two children, orphaned that day? We’re seeing the first queasy suggestions that these rights may be eroded away when we leave the EU. Maybe they won’t be. But I fear that it will be only if we fight for them once more. So, here is this, another memory that shows that once we did fight through, and having done it once, we know we can do it again.

Notes:

[i] Fiona MacCarthy William Morris: A Life for Our Time (Faber & Faber, 1994), p. 568

[ii] EP Thompson William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary (Spectre, 2011), p. 490

[iii] MacCarthy, p. 568

[iv] Rachel Holmes Eleanor Marx (Bloomsbury, 2014), p. 299

[v] Taylor, p. 490

[vi] Holmes, p. 299

[vii] Taylor, p. 490

[viii] Ibid p. 491

[ix] http://spartacus-educational.com/Jcrane.htm, retrieved 8 November 2016

[x] MacCarthy, p. 573

Images:

- Illustration from the Illustrated London News, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1887BloodySunday.jpg retrieved 8 November 1887

- http://www.andrewwhitehead.net/political-pamphlets.html, retrieved 8 November 1887

Tonight is Halloween, and it’s supposed to be the night when the fair folk rise up out of the hollow hills and ride through the lands of the living. If see them dancing and step into the ring to dance alongside them, you could be caught forever… There are many dangers for the unwary mortal stepping into the Otherworld, but less is said about those poor creatures who by chance step out of that world into ours. What if you didn’t want to come to the mortal world? What if it was an accident? Just two children strayed away from their homes, lured into a tunnel by the sound of pretty bells, only to awake in the blazing dawn to a land of strangers, fear and death.

Tonight is Halloween, and it’s supposed to be the night when the fair folk rise up out of the hollow hills and ride through the lands of the living. If see them dancing and step into the ring to dance alongside them, you could be caught forever… There are many dangers for the unwary mortal stepping into the Otherworld, but less is said about those poor creatures who by chance step out of that world into ours. What if you didn’t want to come to the mortal world? What if it was an accident? Just two children strayed away from their homes, lured into a tunnel by the sound of pretty bells, only to awake in the blazing dawn to a land of strangers, fear and death.

But what were they for? I knew it was a play, of course, but I was intrigued by the title, ‘The Green Children’. Who – or what – were these children, and why were they green? I was too young to go to the play and find out for myself, but Mum must have told me the story. It was one of my first encounters with the county’s folklore, and I loved it, even though it was a sad tale. It stayed with me ever since, helping develop a fascination with fairy lore and the Otherworld that lasts to this day. The sad fate of the green boy particularly affected me – and still does, I confess. As a child who was uprooted from my home several times, I admire the green girl for getting on with it, knuckling down and fitting in, but I was like the green boy, lonely and pining for a time and place where I was comfortable…

But what were they for? I knew it was a play, of course, but I was intrigued by the title, ‘The Green Children’. Who – or what – were these children, and why were they green? I was too young to go to the play and find out for myself, but Mum must have told me the story. It was one of my first encounters with the county’s folklore, and I loved it, even though it was a sad tale. It stayed with me ever since, helping develop a fascination with fairy lore and the Otherworld that lasts to this day. The sad fate of the green boy particularly affected me – and still does, I confess. As a child who was uprooted from my home several times, I admire the green girl for getting on with it, knuckling down and fitting in, but I was like the green boy, lonely and pining for a time and place where I was comfortable…